As I assume the role as Executive Director of the Associated Church Press, I’d like to reprise the very first editorial I wrote for United Church News upon my hiring in 2008. These introductory words set an editorial tone that would follow me through several iterations of publications — print and online — at the United Church of Christ, into a freelance career in faith-based media, back to denominational news with Presbyterian News Service, and into today.

As I assume the role as Executive Director of the Associated Church Press, I’d like to reprise the very first editorial I wrote for United Church News upon my hiring in 2008. These introductory words set an editorial tone that would follow me through several iterations of publications — print and online — at the United Church of Christ, into a freelance career in faith-based media, back to denominational news with Presbyterian News Service, and into today.

With gratitude I take on the task of working with an amazing membership and a talented board at the ACP, all who have in their best interest the continuation and excellence of religious journalism, communications and truth telling. I am equally thankful for my friend and colleague, Joe Thoma, who, as the previous Executive Director of the ACP, has been an invaluable resource and helpful guide in the leadership transition.

Future columns will attempt to put into context the role the Associated Church Press and faith-based journalism can play in shaping the dialog around the important issues of our day. But for now, excerpted from the October-November 2008 issue of United Church News, is “In the margins: We follow roadmaps of well-intentioned scribbles”:

When I first entered college I was thrilled with the entire experience. Selecting classes, meeting classmates and professors, navigating the different departments, and best of all — a trip to the campus bookstore. However expensive that last activity turned out to be, I was determined to buy new books when possible.

Carefully handling these pristine volumes in preparation for their first reading, I can recall the decisive “snap” heard when the binding glue of these books was exercised the first time. (Trivia: That sound is the origin of the phrase “cracking the books.”) These new tomes, solely mine and unsullied by other students, would be my gateway to years of formal education.

But as I made my way through two colleges, graduate school and seminary, both my budget and learning process began to have a fuller appreciation of used books. Not only were these “experienced” texts significantly cheaper, they held the untold secret knowledge of previous owners.

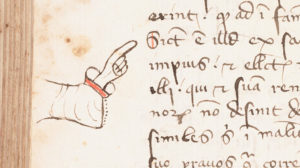

Anonymous learners had scribbled, drawn, underlined, highlighted and charted the most useful information I would need as a student. They provided a roadmap to the important facts and insights needed to succeed in each class. They introduced viewpoints from other professors who may have used the same text, brought clarity to confusing concepts and regularly injected humor into otherwise unexciting topics.

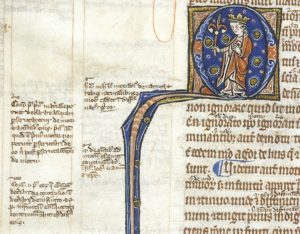

Margin notes also play an interesting role in the Christian tradition. Monastic scribes often inserted margin notes when transcribing or translating documents. Some notes referenced grammar or comparisons with earlier versions of a document. Other notes were of a more reflective or interpretive nature. A monk’s observation on contemporary meaning or application to spiritual life might even make its way into new versions of the document. On occasion, these marginal comments conveyed jokes — and a surprising number of flatulence references — for the reader or the next monk sitting at the copying table.

I also keep close at hand the fuller meaning of the word “margin.” It denotes something outside of the main context, something less important than the primary or something easily discarded. When we say Jesus’ ministry was most often with those who lived in the margins of society, it informs our purpose. Movement into the margins is quite possibly the most challenging call for today’s church — to identify, serve and include those who have been marginalized.

Just as I learned to appreciate the scribbles in used textbooks — and as centuries of Christian tradition was transmitted, explained or embellished by monastic margin notes — so, too, our identity as Christians in culture is clarified by our frequent and intentional excursions (or total immersion) into the margins. Without insights from the margins of society, our experience would be like the new textbook — a little too clean, overly sanitized and ultimately empty of context.

(Note: Since writing this article in 2008 I’ve enjoyed learning how margin notes were used by scribes in many religious traditions – Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist and others. Almost all of them employed humorous references to bodily functions.)